In this edition an interview Tomoé Hill about her wonderful new book, Songs for Olympia out now from Sagging Meniscus Press

BTZ : Could you tell us a bit about your background, where you grew up, your education and how you got into writing ?

TH: I was born in and spent the first half of my life so far in Wisconsin. It wasn’t the smallest city, but it felt small. I found it uninteresting, but that probably had to do with not fitting in (or at least feeling like it). I had a fairly standard education: regular public schools, but owing to a combination of stereotype—being half-Japanese—and learning to read extremely early, reading adult-level at the time I was in kindergarten, I was moved up grades and put into ‘special’ programs, which was somewhat disastrous. Then I had a brief—blink and you’ll miss it brief—stint at art school, where I got kicked out. I drifted after that, working, travelling, and doing some night classes in literature, psychology, philosophy. On a whim borne of a desperation to escape, I applied as a mature student (I was only about five years older than the others) to a UK university to study philosophy, on the logic that they wouldn’t put as much emphasis on my grades because they probably wanted to fill international quota. I got in and then got out of the US.

Writing: I’d played here and there, never really thinking you could have a career in it (and let’s clarify: I don’t, I wish, etc). I grew up in a place where jobs were jobs: offices, factories, schools. Careers were the domain of the wealthier: lawyers, doctors. Even at university, writing numerous papers every week, it didn’t occur to me to write creatively separate to that. It was suggested I go into banking/finance with a philosophy degree and I pushed back against the idea. I ended up getting married, building a couple of small businesses with my then-husband during a recession. It wasn’t until years later, around 2014, when everything was falling apart, that I started to play with writing again as I needed something of my own: my labour, my ideas, my control. Everything now really started from those moments, sitting on a sofa with my laptop at 2:AM, thinking there had to be something else, I had to be something else.

BTZ: Can you tell us about the publications you have written for and your areas of interest in terms of writing?

TH: When I started, I didn’t know what I was doing. I was writing to see what emerged. Eventually, I realised I had something of a voice on the page and in shaping it, I gravitated towards (to reduce it somewhat) the self and observation. I tend towards the sexual, sensual, and longing in various contexts because I think they’re present in most things, obvious or not. Someone early on suggested I write about perfume, and that really started me on essays properly. Later on I found myself playing with the form a little more, going from longer form to reducing it in an attempt to capture an essence on the page. I do both in the book.

I joined social media in 2014 because I didn’t know anything or anyone, coming out of my previous life. I was really only looking for fellow readers, and I stumbled into the London and international indie scene. minor literature[s] was one of the first places to take me in and they really deserve all the credit for supporting me unconditionally over the years. I was an editor there as well as writing for them and it showed me how powerful it was to work collaboratively and with no constraints. Douglas Glover at Numéro Cinq, Andrew Gallix and Joseph Schreiber (when he was there) at 3:AM were likewise important. No one at any of these places blinked when I was writing about sexuality, whatever the context. On a slightly larger level, I had a spell at The Amorist, Rowan Pelling’s short-lived magazine after Erotic Review, where I was doing both solo reviews and a joint monthly review feature with a co-writer: all erotica or related, classic and modern. That was a fun time and I learned some practical/professional things about writing. But mostly, It’s been about indies or places that came about from wanting to do something different: they liked my style and what I wrote about. The Quietus, Mónica Belevan’s Lapsus Lima, Greg Gerke’s Socrates on the Beach, Vestoj, Ligeia, Adam Moody’s new venture The Hobbyhorse, and of course Exacting Clam. I have all the time in the world for indies. They gave me a life I needed and didn't know was possible.

BTZ: Before we speak about Songs for Olympia which is a response to Michel Leiris' The Ribbon at Olympia's Throat - could you tell us about Michel Leiris and your interest in his work and writing?

TH: I came to Leiris late, but I immediately connected with the writing: that intense internal observation, the external observations that seem to circle back to the self. The moments of anxiety and loathing that are natural but tend to be repressed now unless it’s valuable to the personal brand. Nothing about his writing felt in thrall to that concept, and he certainly has times where he’s despairing of writing. His recollection of memories and dreams felt parallel to how I felt, despite the obvious chasm in terms of years. The constant conversation between the internal and external selves that exists in Leiris felt familiar to me. Observations of the world are observations of the self. Finding Leiris was realising another facet of myself.

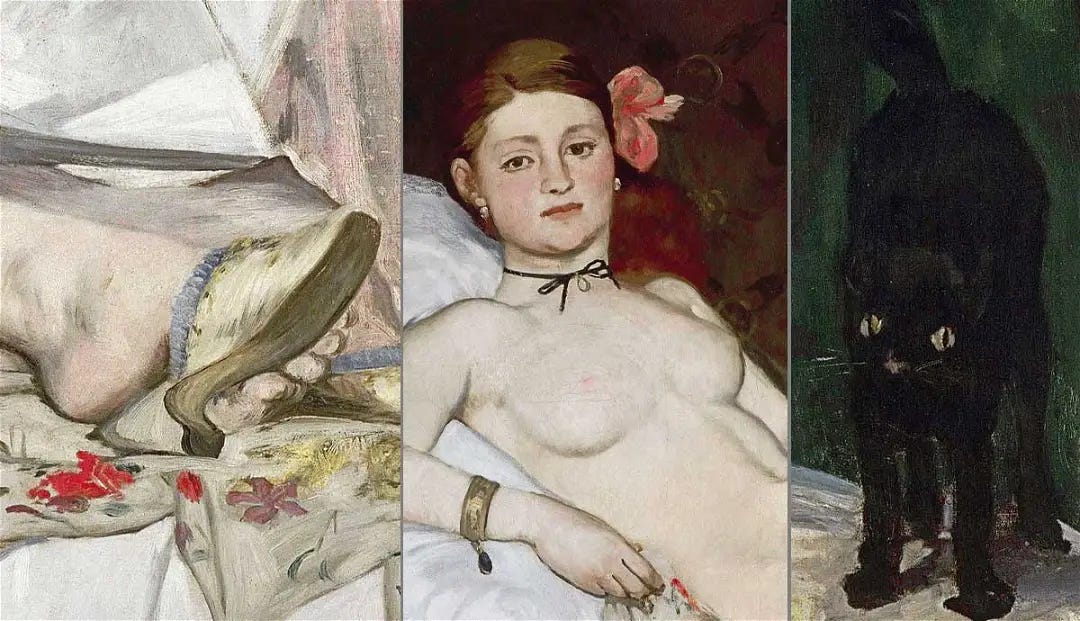

BTZ: The work at the centre of both of your books is the nude painting by Manet, Olympia (1863). She is only wearing a ribbon around her neck and which accentuates her nudity. At the time it was considered by many to be basically porn and a number of details in the painting suggest she is a prostitute. In your book you tell us about seeing this painting for the first time when you were 6. Can you describe this experience and your connection to the painting and the model for the painting?

TH: Of course at that age I had no concept of the idea of social constructs around sexuality. I think somewhere in my mind I had my own forming around all the images that centred around nudity and women in the art books I was looking through, but they were first and foremost an admiration that discounted the presence of men, when they were there. It was her look more than anything: the directness of it. Often the women of paintings were looking away, or at the object of affection (as I saw it then). Now, I’d seen this elsewhere with Goya’s Naked Maja, but that was different—something about its softness meant it was easy to take it in and turn the page, forget. Olympia has an intensity about her, a directness that pierces the viewer, looks straight into, through them. Even I felt it, and while I didn’t understand it, it struck me as innately possessive. It was her gaze. As I grew up and realised the constructs arounds sexuality and how I, too, was seen, I think what continued to appeal was despite that Victorine Meurent, the model, is seen as representing a prostitute—a woman reduced to transaction—there is nothing in her look that says she will be owned. She is wholly herself.

Your book is written as a response to Michel's book. Can you describe his relationship to the painting and what inspired you to respond to The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat ?

It’s worth noting that his relationship with Olympia in terms of the book is an abstract one. Olympia—or rather, the ribbon—is, as Lydia Davis notes, representative of fetishism. Olympia for Leiris is a means of unravelling his life on the page. Her ribbon leads him everywhere from sexual recollections to ones of writing, modernity, and mortality. Going back to the question of my interest in Leiris, when I feel an instant connection to someone’s writing, I want complete immersion. When I read The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat, I was having a conversation with him in my head—probably a bit strange, I know. My experience of Olympia and his book converged and I knew I wanted to do something that spoke to, with him while writing a parallel unravelling of my own.

BTZ: Your book mixes personal anecdote, narrative, art theory, history, and it makes us question how we respond to art and also the woman featured within the frame of Manet's picture. Your prose is rhythmic and lyrical and you use the ribbon around Olympia's throat as a device to explore a range of themes. You also use photos and illustrations throughout the book. Can you tell us about the format of your book and some of the themes you cover?

TH: I deliberately wanted to mimic and respond to Leiris’s form and writing at times while retaining my own voice. Because of that I move between more standard personal essays that echo/update some of his subjects like modernity or rage, but in others, especially desire, I speak directly to him (any use of ‘you’ is to Leiris), sometimes confrontationally, sometimes playfully. There’s a section where I take one of his, which is a kind of abstract wordplay, and challenge it with my own. At other times I use slightly abstract fragments to pull from my own memories or interpret artwork and literature, or try to distil a feeling through aphoristic sentences. The point of the different forms in Songs is meant to achieve what I think he does in Ribbon; the following of the ribbon becomes almost like a dance through memory and thought. At times it should be light, almost teasing, sometimes you feel the smoothness of an observation before your eyes, at others, you feel the pull when something has difficulty in coming undone. An example of the latter would be where I take his original line ‘my father gave me rubies’ and turn it into ‘my father gave me necklaces’ then talk in the following two section about the complexity of living the life you should but in the peripheries, wondering about the life you could have pursued, the meaning of objects as future holders of memory. I illustrate that with a photo of the necklaces he was wearing when he died, that I was given – the tangle of fine leather cords which parallel the ribbon. I would have liked to put in a lot more photos, but there definitely would have been rights issues. I wanted the reader to be able to see what I see, the images that spark words and the words that spark images; an eternal conjuring.

BTZ: One question I want to ask you about the painting is the cat because I think it deserves a book of its own. I think it is such a funny image in the painting especially the cat's expression and body language so would love to hear your thoughts on what it represents or why you think it is included?

TH: At the end of the day it can only be speculation, but I’d like to think Manet had a sense of humour and gave us a somewhat shocked actual pussy as a wink to the one discreetly under Olympia’s hand. If you want to take it further, anyone with any knowledge of cats knows they do precisely what they please. They make you aware of their presence, often not subtly, watch you with a directness which also hides what they are thinking, demand attention that they are also just as happy to abruptly walk away from. If that cat isn’t a metaphor for women’s sexual agency, then I don’t know what is.

BTZ: Can you tell us about your use of personal anecdotes throughout the book especially some of the experiences you had as a child. I felt these give the book a real personal touch.

TH: Something I was going for generally was that each section should be approached as a painting in a gallery. Each is its own work, but they have an overall theme. Within that, you could say that the personal anecdotes about childhood are meant to be looked at by the reader like they are looking through a photograph album. That’s perhaps ironic considering I have a near-phobia of having my photo taken or even being seen ‘live’ outside of friends as an adult. I can take my own, though I don’t particularly like that either – I consider it a necessary evil in our very online, visual society. I also have a tendency to look at parts of my life with a lens distance (again, I’m aware of the irony). I liked the idea of snapshots of random moments, though these are also particular moments that have burned in my memory with everything from shame and euphoria, curiosity and realisation. Rather than a complete chronological narrative I thought within the context of Leiris’s form in Olympia, those snapshots would burn on the page as well. A landscape is lovely, but I’ve always preferred the intensity of detail that leaves you having to figure something out like a puzzle. I reveal, but only in a deliberately obscured way.

BTZ: One of the other things you did for this book is feed The Manet painting into an AI app called I Magma as a way to see Olympia in a new way - can you tell us about that process ?

TH: (this explanation can be read in full at: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/jenna-sutela-i-magma-app/). I Magma (the app) is an extension of the installation by artist Jenna Sutela that was in Stockholm from 2019-2020 at the Moderna Museet. It ‘features a series of custom made head-shaped lava lamps whose movements act as a ‘seed’ in generating the app’s visuals and language. Using live camera footage of the lava flow in combination with the routes of app users, it allows the users to receive divinatory readings based on collectively formed shapes. The Serpentine commission (the app) expands Sutela’s research into alternative forms of intelligence by applying chemical and digital processes in the creation of an oracle, accessed via an app from mobile devices.’ You take a photo of something, and the app processes it—complete with lava lamp bubbles while you wait—then gives you a manipulated version of the image back with a message. I mean, it’s all a bit of fun. I learned about it through reading about some of her other work at the time I was writing the book, and I thought, oh, why not. I did it twice, and I won’t say here what I gave it or received, but it was a serendipitous moment, so much so that it became part of the book.

BTZ: Can you tell us about some of your gateway books - books that have inspired you as a reader and writer ?

It might be more of an insight to tell you about the books I encountered as a fairly young child rather than later on which continue to inform how I see the world, and so, write.

1. Look & Learn: this was part of something called the Childcraft Encyclopedia series. It was full of odd information and observations on everything from the old hidden meanings in giving flowers, how to look at negative space, and why advertising distracts us from our intentions. I think it was my introduction to being aware of connectivity and meaning in absolutely everything.

2. The poetry of e.e. cummings: my parents had a collected edition, which was the first adult poetry I ever read. Aside from the obvious shock of the style, which can be abstract and deliberately ignoring any ‘rules’ of grammar or punctuation – a surprise for a child then learning nothing but rules – the atmosphere of them affected me intensely. This is contemporaneous with me discovering Olympia, and I felt something in his poetry which I later recognised as a sense of the romantic, the sensual, but presented in a very different way to how we tend talk about those things (within the social construct). He writes desire as fragmented and dreamlike but still expressing the magnitude of emotions.

3. The Mind: this was part of another series, Time Life—Medical, I think. Parts of it are wildly dated, but reading about everything from the connectivity between the senses and brain, how we compensate or reroute when there is a disability, to the history of the treatment of mental health, and other things like Descartes and the pineal gland was like another world.

4. The World in Your Garden: this was just a lovely old (maybe 50s? 60s?) book of photos and text about gardens and flora from around the world. We had a chaotic back garden growing up, with everything from bleeding hearts and foxglove, grapes and currants, marigolds and physalis. The two hand-in-hand were formative in my relationship with my senses.

5. The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster. You’re probably thinking, finally, a normal kids’ book! I loved this—I still have my original copy. It’s full of language, numeric, and logic play, as well as quite wise observations on human nature and how we perceive others. Despite its presentation of the basic storyline, there is nothing juvenile about it—it is a story about dissatisfaction with the artifice of the modern world and the beauty and complexity of exploring your imagination.

BTZ: What books are you currently reading, have recently enjoyed or are looking forward to ?

TH: I’m a re-reader as much as anything—I get a huge amount of pleasure going back to books. I’m re-reading Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin, which is essentially a book on architecture along the lines of Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space or Susan Stewart’s On Longing and The Ruins Lesson. He writes so beautifully about the connectivity between the senses, philosophy, art, and literature to the main subject that I find it simply an intensely human book. I go back to it a lot, and used a quote for the epigraph of Songs for Olympia. Infinity Land Press just published Death Poems by Jacques Prevel (tr. Tobias Freeman). Freeman writes a beautiful introduction where he talks about the relationship between Artaud and Prevel, his perpetual outsider status, and his poems being anti-poetry, in a way. I’m always attracted to people like that, because I am one. Prevel’s poetry is at times fractured and arrhythmic, so bare it feels painful on the page, yet beautiful in its simplicity. It also has the bonus of gorgeous intricate illustrations of hearts (the organ) by Karolina Urbaniak.

I’m also re-reading Abysses and The Fount of Time by Pascal Quignard (tr. Chris Turner) in anticipation of The Unsaddled (tr. John Taylor) from Seagull Books arriving. Quignard is a favourite of mine for his delicate fragments on everything from art and nature, desire and philosophy. I’m looking forward to the release of Cesare Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò (tr. William Arrowsmith and D.S. Carne-Ross) from Sublunary Editions and Skeletons in the Closet by Jean-Patrick Manchette (tr. Alyson Waters), from NYRB Classics. And Dalkey Archive recently released Violette Leduc’s La Bâtarde (tr. Derek Coltman), which was just in time as my old Panther edition was falling apart, so I’ve been enjoying that all over again with the extra pleasure of not having to handle it with any delicacy.

BTZ: What are your Desert island books ?

TH: Oh, I hate these book questions—sorry, I am laughing as I type that. It’s only that I completely freeze whenever anyone asks me something like this in person, and then it looks like I don’t read! Indulge me—I’m going to be completely difficult to finish. My favourite books, by which I mean the ones I read repeatedly at the point in my life when they are of importance, I find are so ingrained that I can repeat passages from memory. What I do I need to bring them for? So let’s forget the Quignards, Leducs, Zolas and the rest, here’s what I would bring:

Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin, Leon Battista Alberti’s On the Art of Building in Ten Books (tr, Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, Robert Tavernor), and the dictionary. My reasoning here is that Pallasmaa and Alberti’s writing is as much about being as buildings. If I’m on that island, I’m going to be spending a lot of time writing (and I’m going to need shelter), so what better to have to hand than those?

Oh, and if I can bind up all the letters and messages I’ve written to lovers and their responses, that’s all I would need. They might exist in the depths of my body but the pleasure of rereading them on the page is like watching a bud burst into flower over and over. After all, I’m going to need to relax after a hard day of writing and building.

Tomoé’s website is

https://www.tomoehill.com and she is on

X @CuriosoTheGreat

Bluesky: @curiosothegreat.bsky.social

Email: curiosothegreat@gmail.com