A very Merry Christmas, Happy Chanuka and happy new year to everyone. A huge thanks to all of you for your support over the year and especially to the people who support the podcast on Patreon. I hope it has been a great year of reading and wishing you all a 2024 full of great books, creative output and happiness.

On the last Substack for the year, I recently interviewed Évelyne Grossman about her book The Creativity of The Crisis. It is out now from Contra Mundum Press.

Évelyne Grossman is a professor at the University of Paris, former president of the International College of Philosophy, editor at Gallimard of Antonin Artaud’s works and she is a specialist in literary theory. She situates her work at the crossroads of literature, philosophy, and psychoanalysis.

BTZ: Could you tell us a little bit about your academic background and your work as a writer and editor?

EG: I studied linguistics and comparative literature mostly at the University of Paris Initially I was interested in the work of Julia Kristeva, with whom I did my dissertation on "James Joyce, Antonin Artaud: the body and the text", I was above all nourished by psychoanalysis and continental philosophy, in particular Derrida and Deleuze-Guattari.

I went on to teach comparative literature (particularly at the intersection of literature, philosophy and psychoanalysis), first at the University of Bordeaux and then as a Professor at the University of Paris Cité (formerly Paris 7- Paris Diderot), where I did most of my studies.

In the early 2000s, Gallimard asked me to persuade Artaud's nephew, who had had the publication of his complete works abruptly interrupted for various reasons, to resume this work. This is how I came to publish many of Artaud's works with Gallimard, some of them previously unpublished, and in particular the large volume of his Oeuvres in the Quarto collection.

This volume, which restored Artaud's work to its chronological perspective and presented the poetic and political issues at stake while respecting his creative madness, made his work more accessible to a wide audience, particularly students, who had been somewhat lost in the 27 (incomplete) volumes of his works published until then.

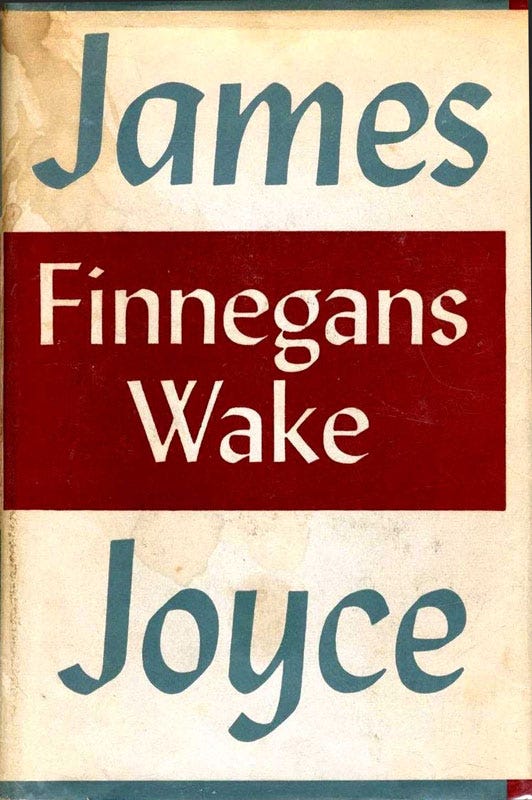

My own work as an academic and essayist has been nourished by this experience of reading works that are considered to be difficult to access or even “mad” (it took me a year to "read" Finnegans Wake...).

Everything I've published so far continues the reflections I've had from the outset on issues related to the vulnerability of thought, the hypersensitivity of the body, and the fertile instability that drives many contemporary texts and works of art as they explore the relationship between the human and the non-human.

BTZ: La Créativité de la crise came out in French in 2020 and it is out now from Contra Mundum in English. The work focuses on the role “crisis” plays in the creation of art and you exemplify this concept and how it affected a range of artists, philosophers and writers. Before we speak in more depth about book itself could you define the word crisis as you use it in the book?

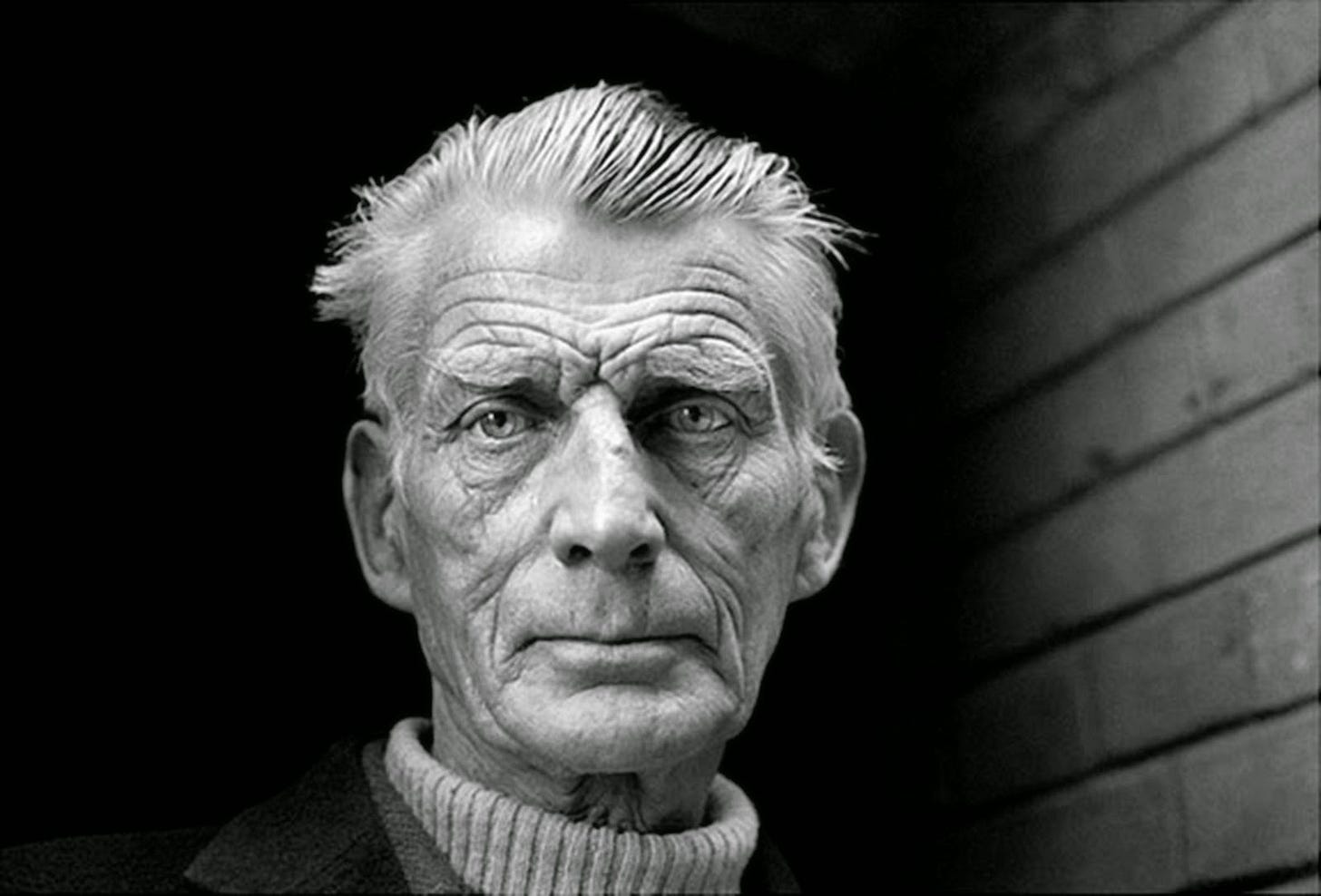

EG : I think that the term "crisis" is nowadays much eroded and we need to reactivate it to hear it again. A first definition would be: crisis is separation, rupture of equilibrium. Already, in Hippocratic medicine, the crisis (krisis) designates the crucial phase in the evolution of a disease toward aggravation or recovery: decisive moment of uncertainty. The authors or philosophers I mention in the book (Antonin Artaud, Samuel Beckett and Friedrich Nietzsche, among others) are no strangers to this idea of crisis. Not only because they were confronted with the more or less severe risk of psychic collapse but because they can help us to better understand the so strangely indissociable relationship between crisis and creation. To a certain extent, I want to show that, contrary to popular belief, we only write at the cost of a preserved imbalance, in the endurance of insecurity.

BTZ: The book is split into three sections – Crisis of Creativity, The Impersonal as a creator and Creativity of crisis. In the first section you introduce us to Artaud as a young poet and after he has sent his poems to an editor and he describes the metaphysical abyss he falls into creating art. You explain that this kind of crisis is not simply writers block in our modern sense but a true torment of the soul can you tell us about that idea and also about Antonin Artaud?

EG: As I explain at the start of the book, when the young poet Antonin Artaud sent his first poems to Jacques Rivière, the director of the prestigious "Nouvelle Revue française", forerunner of Gallimard, he wrote in famous terms of the "appalling illness of the mind" from which he was suffering, the powerlessness of thought which suffocates him: not a simple crisis of inspiration, he underlines, but a true deperdition of being. But the dark chasms where Artaud sometimes descends are fortunately very far removed from the ordinary torments of creation, those that everyone can one day cross.

Artaud is the very emblem of the mad, genial writer (a Romantic concept that is not extinct, as we can see) who confronts forces of dissolution that are fortunately alien to ordinary mortals. Yet he helps us to understand the depths of the abyss that can be opened up by the vertigo of creation.

BTZ: Many modern writers had a similar crisis of creativity, and you speak about Barthes in the same way as he struggled to write a novel. Can you tell us about some of the other writers you explore within this section of the book?

EG: More modestly, but closer to us, the crisis of creativity (whether in literature or art in the broadest sense) that I'm talking about is widely shared. Roland Barthes, for example, the great theorist of desire and creation, wanted all his life to become a writer, but never succeeded. He knew perfectly well that a literary theorist is hardly the equivalent of a true writer, in the classical sense of the term, like Chateaubriand or Tolstoy, two of his models. Nevertheless, he dismissed with irony the literary myth of “the fertile crisis” or the “central crisis” from which the triumphant Work leaves regenerated. He perfectly knew that all creation originates in the complexity of the erotic process, in the Freudian sense of the term: it puts desire and its powerlessness into play.

We can mention Beckett and Kafka, of course, but also Deleuze.

BTZ: In the second section of the book you move onto the way the removal of self was inspirational for people like surrealists and methodology like automatic writing assisted with the creation of art can you tell us more about this idea?

EG: One motive is for me essential: you never really know who is writing; not who am I, I who write, but what, inside or outside me, writes. This is a question, bordering on madness, which Beckett or Blanchot, among others, will take up. The Surrealists, whether writers or painters (Breton, Soupault, Dali), bet on the liberation of the creative forces of a pre-subjective, pre-personal unconscious, capable of sparking off words and images in abundance and without any neurotic blockage.

BTZ: In the third part of the book the book we return to Artaud and also to Beckett among others and you explore the notion of separation and externality inspiring their work. Becketts’s works especially the Molloy trilogy gives us that idea that the experience of life is often done in an almost dream like - observer perspective. Could you tell us more about this idea and also your experience reading writers like Beckett?

EG: We are a failing creation, Beckett suggests. Creation is a divine slip that we are condemned to reproduce. Beckett is perfectly familiar with the Freudian lesson: failure is an indisputable form of creation; it is with this failing that we write. We don’t create contra failing, with create with failing.

This is Beckett's great lesson (but also Artaud’s, Deleuze’s and many others): failing is a creative process that forces us to rethink our overly simple categories of success and failure. “Fail better”, as Beckett puts it.

BTZ: One of the things that fascinated me about this book is the way you speak about the creative process across genres and through the lens of philosophy and psychology. Could you tell us more about the way these concepts intersect in your work?

EG: I’ve always tried to think of art and writing at the intersection of philosophy and psychoanalysis. This is undoubtedly the reason for my interest in philosophers such as Derrida, who, with deconstruction, sought to reinvent a new form of analysis (I'm probably more of an analyst than those who are paid to be, he once said), or Deleuze and Guattari, who invented a new type of conceptual writing for two (à deux mains), experimenting with an unprecedented mode of conceiving and thinking, Deleuze-Guattari, or Nietzsche (the power of disequilibrium at work in his poetic, aphoristic style).

BTZ: You worked with Rainer J. Hanshe on the translation of the book. How was the experience of translating your work into English?

EG: It is somewhat like a psychoanalysis - all things considered: you discover that there was a lot more, and perhaps something completely different, in your thoughts than what you thought you had put there. The experience of switching from one language to another is always fascinating because, most of the time, it forces us to clarify our thinking. I should point out that I merely re-read Rainer J. Hanshe's translation, which was excellent in every respect. He knows the thinkers and writers I mention in this book very well, and his work is outstanding.

BTZ: Which books have you recently read that you can recommend for us?

EG: At the moment, I am fascinated by the writings of trans philosopher Paul B. Preciado. In particular, I have been reading his last two books, An Apartment on Uranus: Chronicles of the Crossing and Dysphoria Mundi his latest book (I don't know whether there is an English edition of the book yet or not). In particular, he shows that the frontier of gender is perhaps, along with that of race, the most violent political frontier invented by mankind. Gender transition, in this sense, is an experience of crossing, of exile populated by a multiplicity of voices, making him a "gender migrant". What I admire about Preciado is that he elevates the debate, as we say; he deterritorializes it, as Deleuze-Guattari would have said. In Dysphoria mundi, a book that is dense, radical, excessive but often luminous, as is often the case with him, he sweeps us along in his whirlwind of Deleuzian-Derridian-Butlerian thought (among others), which is also the wager of a creator eager, despite any "dysphoria", to redraw the boundaries of bodies and lands: life, he says, is mutation and radical multiplicity. Here we find the new ontologies of the living, far beyond any delimitation of genres.

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9781635901139/an-apartment-on-uranus/

I have also been reading Judith Butler's What World Is This?: A Pandemic Phenomenology; I love what they write about the fact that the pandemic compels us to ask fundamental questions about our place in the world: the many ways humans rely on one another, “we exist in proximity to other porous creatures in order to live in a social world”, they write. It is gorgeous with humanity and depth, I think.

https://cup.columbia.edu/book/what-world-is-this/9780231557351

BTZ: What are 5 of your desert island books - books that are your all time favourite books and why?

I would say James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. It is not that it replaces all literature (and certainly not all thought!), but you are never done reading it, and every time you open the book you are reading something else than what you thought you would read. It is an inexhaustible book, in perpetual metamorphosis, in infinite motion.

But one of my favorite writers is unquestionably Samuel Beckett, so I'll also say the following two volumes (which count as four) Three Novels: Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable and The Complete Short Prose of Samuel Beckett, 1929-1989 (S.E. Gontarski editor).