BTZ Newsletter Feb 2024

Welcome to the first edition of the BTZ newsletter for 2024. In this edition we have some news and a short story from Matthew Clayfield.

Book News

The most exciting news this month is the announcement of Sergio De La Pava’s new novel, Every Arc Bends Its Radian. It is slated for release on November 12 and it is 288 pages.

Here is the description from the publisher :

From PEN Award–winning author Sergio de la Pava comes an existential detective novel about a private investigator who flees New York City for Columbia after a personal tragedy and finds himself entangled in a young woman’s strange disappearance—which may be connected to one of the world’s most ruthless criminal organizations.

Riv—poet, philosopher, private eye—arrives in Cali, Colombia, hoping to find nothing. Running away from his family and an unspeakable event surrounding his ex-wife Jane, Riv accidentally connects with his cousin Mauro and great Aunt Corelletta who asks him to find her daughter Angelica Alfa. No sooner is Riv on the trail when it becomes clear that not only are the cops not looking for Angelica, but they are actively preventing him from finding her. This could be a good thing because the police are clearly in the pocket of one Exeter Mondragon, a name best never uttered in public if one wants to stay alive. But Riv is not one to leave things incomplete. When his investigation leads him straight into the heart of Mondragon’s criminal empire, he is forced not only to face unimaginable horrors, but also to plunge into the deepest and most perplexing conundrums of the human condition.

Lightning fast on the page and steeped in the cultural history of Columbia, Every Arc Bends Its Radian is a novel only Sergio de la Pava could write. As incredibly funny as it is ridiculously smart, it poses large philosophical questions while keeping you laughing. A novel idea about the biggest idea of them all—what in God’s name are we even put on earth for, this book is a singular exploration of the human mind.

Obviously I cannot wait to get my hands on this and I am confident Sergio will return to the podcast later in the year. Stay tuned.

Blake Butler has a new novel that sounds insane UXA.GOV it is out August 2024

Geoffrey D. Morrison’s has sold a new novel - The Coffin of Honey, a digressive, polyvocal novel with speculative, surreal, and philosophical elements, recalling Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Thomas Pynchon, and Can Xue.

Kieran Goddard just released I See Buildings Fall Like Lightning. I read this over the weekend and it well worth your time.

Manya Wilkinson just released Lublin from And Other Stories really looking forward to reading this.

A recent release I am very keen to read is How I Killed the Universal Man by Thomas Kendall They also have David Leo Rice’s The Berlin Wall available for pre-order here

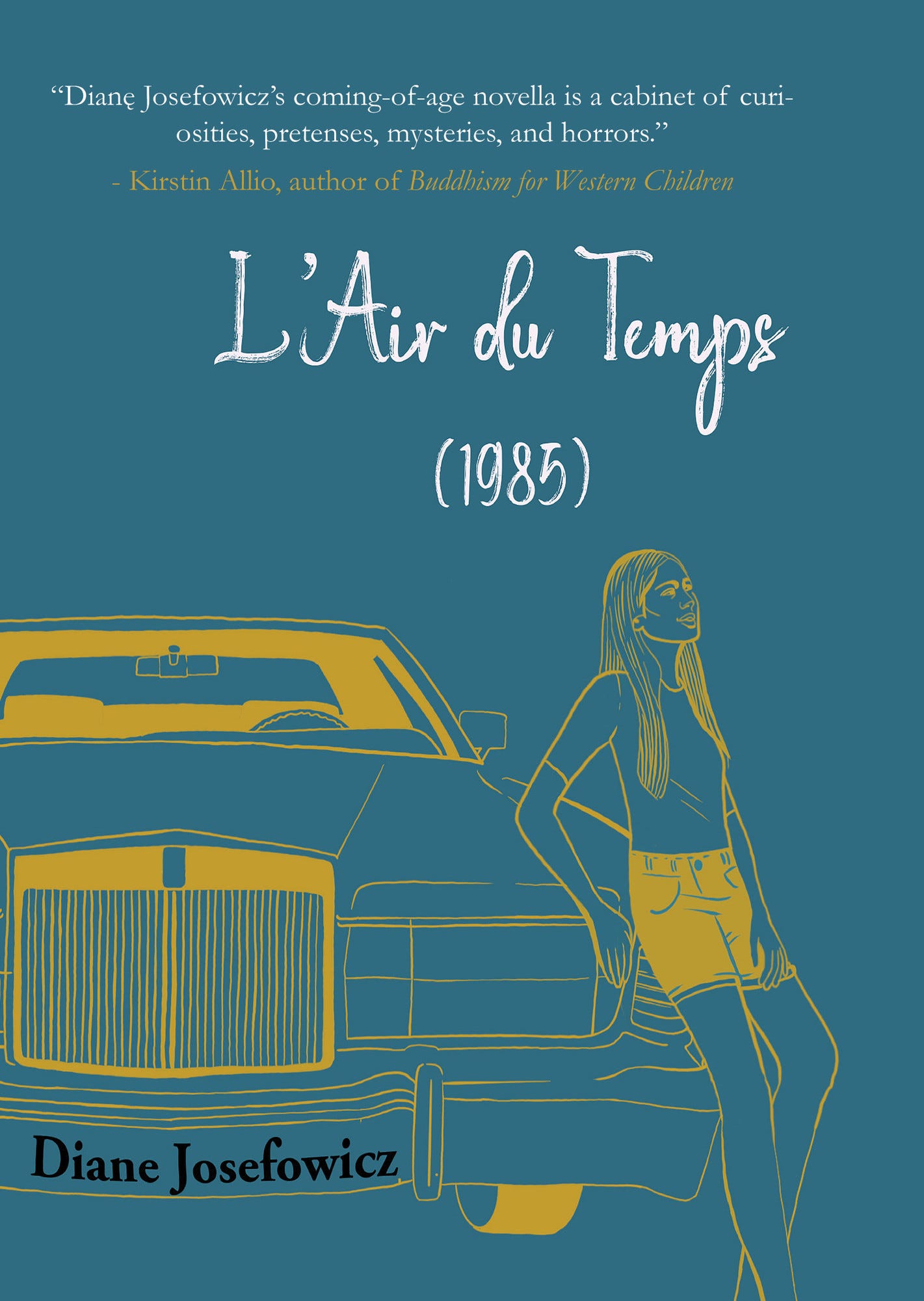

In other news L'AIR DU TEMPS (1985) by Diane Josefowitz is out from Regal House on the 12th of March.

Also really excited to read Ben Tanzer’s The Missing and A Brutal Design By Zachery C Solomon. Also upcoming is Otohiko Kaga’s Marshland (April) and Children of the Dead by Elfriede Jelinek. Through the Forest by LAURA ALCOBA is out now from F’dE as is Atlantis by RONALD PUPPO and don’t forget the Bar Mitzvah edition of The Instructions by Adam Levin

If you have book news or a review or essay feel free to send it in to beyondthezeropod@gmail.com

Short Story

The Suicide Hotel by Matthew Clayfield

@mclayfield

It was one of those stories that I sometimes pitched to make sure that I had money coming in: a throwaway that meant nothing to me, but which was curious enough that an online magazine would run it in return for my small fee. The money would keep me in drink a week, while I did the real work that paid even less, and I would be able to pretend a little longer that I was a journalist and that what I was doing mattered. More importantly, though I would not have put it this way at the time, I would be able to keep moving.

It was never hard to find such stories. Every town or city has one. Sometimes you'd find it in the local paper, double-checking to make sure it had not yet gone viral, and other times it was whispered across the bar on the stale breath of the local drunks. It was only a matter of being open to them. I would head out, meet the relevant parties, take a picture or two on my phone, and make sure I had gotten the quotes around which I might later weave a story. A dab of colour to remind the people who read it that foreigners are strange and the world an inexplicable place.

I had been warned off writing this one, though. The locals who had let it slip to me had told me to reconsider my plans. I had put this down to hometown pride, to the sense that I might do reputational damage. For there was no colour in this colour story at all: it was one that, even handled with a light touch, was likely to capture that light and extinguish it. It was strange, the things that people got upset about, that kindled and oxygenated their loyalty. But in this case I understood their reticence. The story the locals had told me in confidence was about a hotel, somewhere on the outskirts of town, where people went to kill themselves.

It wasn't much to look at from the street, though it had clearly once been something grander. It was a three-story place, like a week-old layer cake, at the end of a cul-de-sac away from the main tourist section. It appeared to be leaning on the building next to it. The windows were blacked out, which suggested it had been shuttered, or that it was a brothel. But the door onto the street, its paint flaking, was open, and I paid and thanked the cab driver for his time, even though he, too, was asking me not to go.

There was a woman hovering between middle and late age on the far side of the counter in the entrance and she gave me a look that suggested she was surprised to see someone like me standing opposite her like this. She appeared to have grown there a long time ago, like an oak tree, or more accurately a toadstool, and surprised me in turn when she was able to uproot herself.

You are not here to check-in? she asked me incredulously, speaking in the local language.

No, I said. I am a journalist. I have come to ask about the stories.

It did not seem that I should lie, seeing that she had already picked me as an interloper. I would wind up asking about the stories anyway, and it was possible that she would get angry at me when she learned about my subterfuge. Then I would not get my quotes for the story, and I would be unable to weave anything but a commentary on my failure, which, although I would be able to sell such an article, would not be as good as the one I wanted to write. I had written a number of pieces in that vein, journalism about the practice of itself, and each one rankled, even now, because however good or funny such pieces were they still weren't the thing but were adjacent to the thing. That I still sometimes used subterfuge, both successfully and otherwise, was a commentary less on the profession than on me, and on how much value I actually placed upon it.

What stories are you talking about? asked the woman.

The stories about the suicides, I said. I told her that I had been told that people came to her hotel to kill themselves.

Why would you wish to tell such stories?

I told her that they were of interest to readers.

They are not interesting, she said. They are harmful.

To your business?

No, she said. My business is successful.

I asked her whether she had any guests, and whether I might be able to meet them, but she said that she was not at liberty to say. I asked her whether I could see one of the rooms and she said that she was sure I didn't want to.

It will be good for my story to see one, I said.

She sighed and took a key from a hook, which had been drilled into the wall behind her alongside many other hooks that also had keys on them.

I think you are making a mistake, she said. They are rooms like any other.

Why do people keep choosing them to die in?

Because they hear that they are good for that, she said. That, she said, was the problem with such stories, and she asked me to leave my notepad on the counter, apparently unaware that I would describe the room from memory. She emerged from behind the counter in a waddle and said she would like her business to fail, that she would like to be able to close it someday, but that she could not do so while people needed her rooms, or at the very least kept learning about them.

Perhaps, she said, you will not write anything, once you, too, have seen the rooms.

Perhaps, I said, though I did not think this likely. This was what I had decided to write, and I needed the money, and so I would write it. Anyway, I thought, the people who would read it were unlikely to come here, inspired by me to do away with themselves. The stories that the woman was talking about were the stories that had inspired me. The people she had a problem with were her neighbours and this would be of interest to readers, too.

We went upstairs to the first damp-streaked hallway and were about halfway along it when she handed me the keys.

I am going to wait here, she said. These open the door at the end of the hall.

I took them from her and smiled, taking her old-fashioned superstition for old-fashioned propriety. We had stopped to make the brief exchange and when I set off again I heard my feet disengage from the carpet. It was the kind of run-down place I knew well, the kind I was staying in on the other side of town, and that it had developed the reputation it had was almost amusing to me. If not this place, another. It had just so happened that, one night long ago, someone down on his luck or money had decided to end it here, and word spread.

The lock was old and the key was rusty, but the door opened without any trouble and hung there. I could see into the space from the threshold, which, instinctively, I did not cross. It was not as dingy as the hallway I stood in: it was rather white, with white furnishings inside it, a vanity to the left and double bed to the right, the former of wood and the latter of cast iron. But it was an old white somehow, as though faded half to grey, reminiscent of the inside of an eggshell or the immediate post-glare dying of a flashbulb. It was clear, the moment I laid eyes upon it, that everyone I had spoken to had been right.

I felt an overwhelming urge to enter, more physical than journalistic, more compulsion than mere sensation. The effect of the room upon me was visceral, like a smell but more totalalising in its effect on the body, and I became very conscious of the joint in my knee as the fluid there rushed to grease the motion that would lead to it bending and thus to lifting my leg. Once that had happened, and my foot was in the air, I somehow knew it would be too late, and that the chain of events that this consciousness of my knee now portended would ultimately lead to me entering the room and shutting the door behind me. The room wanted, for want of a better word, to have me, and I found myself willing my knee not to move, and my feet to remain where they were on the floor, and even then it seemed as though I was moving forward on the spot all the same, as though the carpet itself was moving forward by degrees, and even as I kept my feet planted I turned my upper body away in an attempt to pull free of whatever it was that was in there. And it was like disentangling myself from something, an invisible vine or strong set of arms, and once I was free I even lost my balance, as though something had suddenly let me go.

When I looked up, a good foot or more from the door, the woman was standing where I had left her halfway down the hall.

Don't worry about the door, she said. It is better now to leave the door.

And I noticed another man, as I walked back towards her, standing at another door beyond the staircase, where the hallway continued in the other direction. He stood bare-chested and had a red beard, and when I tried to meet his eyes he rolled them and shook his head and went back into his room.

We returned downstairs and the keys to their hook and the woman asked me whether I was going to write the story. I told her I didn't know. There was nothing particularly interesting about the room, I said, and in any case I had decided not to enter it.

How much do they pay you for stories like that? she asked.

I told her and she shook her head.

That is a lot of money, she said, though it really wasn't that much to me. And people, readers, they read such stories?

I said that they did.

Such people are cruel, she said.

I thanked her for her time and paid her, even though I had not taken a room. I paid her because I was planning on asking her, and did now, who the man in the hallway had been.

He is my guest, she said, as though it were obvious.

And is he going to kill himself? I asked.

She shook her head.

He lives here, she said. He is the only one who has not killed himself in my hotel in many years. Each day he leaves his money by the door and each morning he is still alive.

Who is he, though?

I don't know, she said. All I know is that he scares me.

I spent that night getting drunk in the tourist section, not talking to anyone about the hotel, and the next morning I boarded a bus to the city and the day after that a plane to the next place. This was many years ago now, and I do not practice journalism anymore, having learned that there was no money or glory in it, and that even the stories that mattered never changed anything. It was getting me down, and so I got out, and the story that I wrote about that day was rejected by all the editors I sent it to on the grounds that the lie I had sent them was dull.